Kidney disease is the leading cause of death in cats over 5 years of age. Do you know what causes it or what you can do about it?

What is kidney disease?

Kidney disease (or renal disease) refers to when the kidneys are damaged and don’t do what they’re supposed to do (ie they fail).

What do kidneys do?

Kidneys are vital organs – you can’t live without them. They have several functions:

filter blood to remove metabolic waste products

help maintain adequate hydration

help control blood pressure

produce a hormone (erythropoietin or EPO) that stimulates red blood cell production

help regulate calcium and phosphorus balance

help maintain correct levels of electrolytes (sodium and potassium)

conserve proteins in the blood

help maintain pH levels for optimum metabolic processes

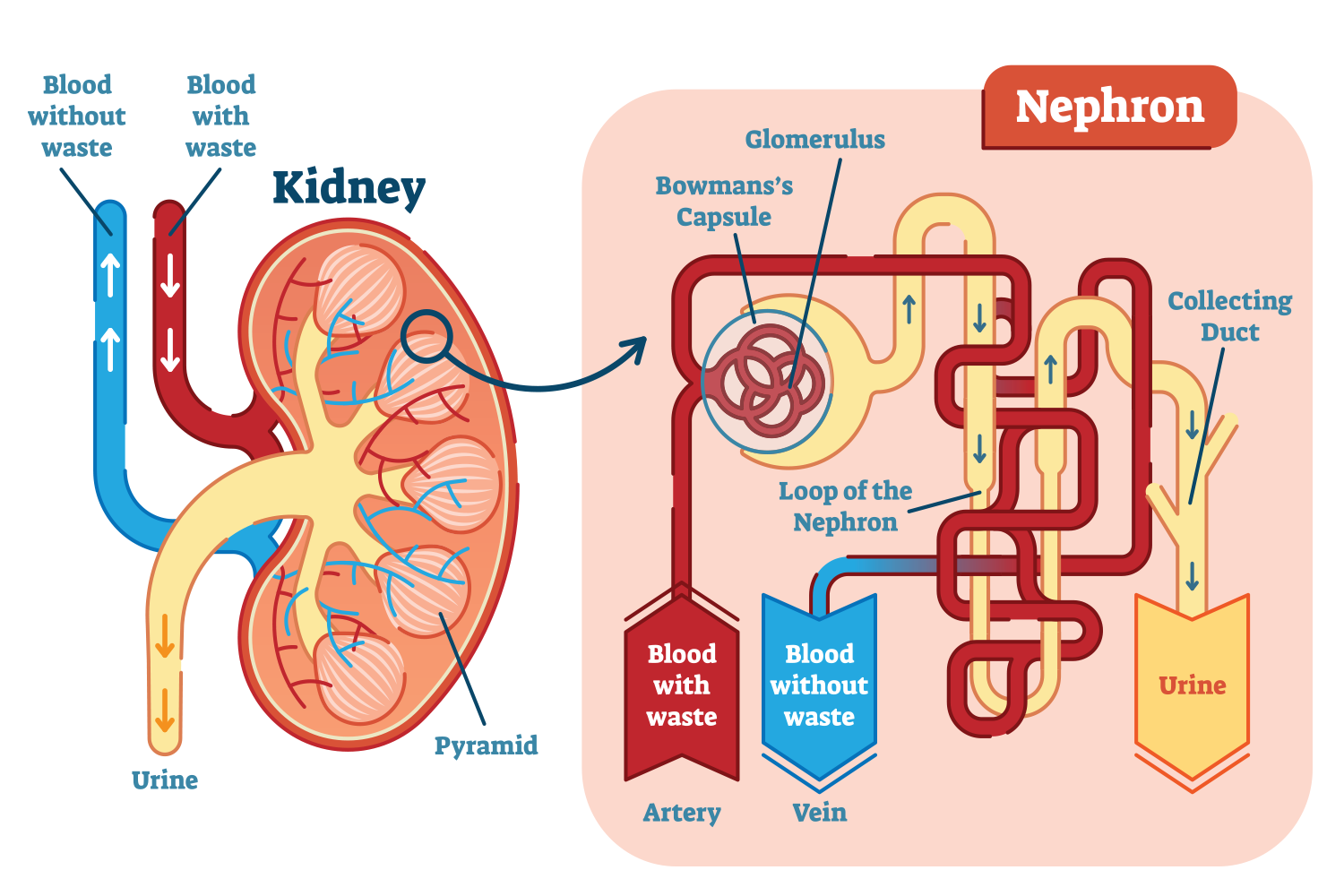

How do the kidneys work?

When it comes to kidney function, the key word to remember is nephron. Nephrons are the ‘functional units’ of the kidney. We’re all born with more nephrons than we need and as we age, nephrons die off by simple wear and tear and through disease. If too many nephrons are lost, renal failure develops – when it happens quickly, it’s acute and when it happens gradually, it’s chronic.

The anatomy and physiology of the kidney

One reason cats are more prone to kidney disease than other species is that they don’t start their lives with as many ‘spare’ nephrons. For example:

cats start out with about 200,000 nephrons in each kidney

dogs have about 400,000 per kidney

humans have somewhere around 1,000,000 in each kidney

We can help our cats live longer lives with good diets and advances in medical care, but we can’t give them more nephrons.

What types of kidney disease are there?

There are lots of different types of kidney disease (eg kidney stones, kidney infection, polycystic kidney disease), but the main two categories that we focus on are:

acute kidney disease (AKD) – which is when the kidney damage happens quickly and the onset of kidney failure is rapid (ie over days). It’s also called acute kidney injury (AKI) or acute renal failure (ARF)

chronic kidney disease (CKD) – which describes slower and ongoing kidney damage (ie over months to years). It’s also known as chronic renal failure (CRF) or renal insufficiency

Note that the terms acute and chronic refer to a time frame and not to severity.

The reason we focus on differentiating between acute and chronic disease is that the medical approaches and prognoses are different. Acute disease can be reversed (if diagnosed in time) but despite advances in treatment, the death rate in animals (and people) remains high. Chronic disease cannot be reversed or cured, although it can be managed and sometimes slowed down.

What causes kidney disease?

acute kidney disease

The most common cause of AKD in cats is ingestion of something that is toxic to the kidneys such as lilies (all parts of the plant), human medications (ibuprofen), snake venom, antifreeze, pesticides and cleaning fluids.

Other causes of AKD include:

sudden loss of blood flow to the kidneys, which can happen with rapid dehydration (eg heat stroke, severe vomiting/diarrhoea), shock (eg from blood loss, sepsis), low blood pressure (eg heart failure, anaesthetic agents) and blockages (eg blood clots)

kidney infection (called pyelonephritis and usually secondary to a bladder infection)

blockage to outflow of urine from the kidneys (eg kidney stones or clots in the urethra)

renal cancer (usually lymphoma)

trauma

Although we know these things can cause AKD, it’s can be difficult to say what the exact cause has been in an individual cat. Especially when it comes to toxins, unless you’ve seen your cat eat something, we can’t say what it was.

chronic kidney disease

It’s much harder to determine the underlying cause for CKD. It’s like looking at old scar tissue and trying to work out what caused the initial injury. Any of the causes of AKD can also cause CKD.

Other disease processes that can lead to CKD include:

polycystic kidney disease (especially in Persians and their crosses)

congenital disease

amyloidosis (build up of protein in the kidneys)

inflammatory disease (glomerulonephritis)

high blood pressure

In an older cat, it’s likely that along with simple wear and tear, several nephron-destroying things have occurred over a lifetime, until there aren’t enough to maintain normal function.

What are the signs of kidney disease?

It’s possible to experience kidney damage but not show any signs of kidney disease. Because we have more nephrons than we need, we can cope with some kidney damage. In fact, people can lose 90% of their nephrons before experiencing any symptoms!

The early symptoms in people are vague (eg feeling tired) and we probably miss these in cats. Later signs include:

decreased appetite

vomiting

weight loss

drinking a lot and peeing a lot (followed by urinating less)

constipation or diarrhoea

bad breath

mouth ulcers

a brownish colour to the tongue

weakness

The signs are the same whether we’re looking at acute or chronic disease – acute disease just has a rapid onset. It is possible for a cat with CKD to develop an acute injury and then we see a sudden worsening of disease. This is often referred to as acute on chronic renal failure.

How is kidney disease diagnosed?

The presence of kidney disease is determined using blood and urine testing. To find the underlying cause, other testing may be required such as ultrasound/biopsy.

Blood testing

Because the signs of kidney disease (eg vomiting) may be seen with other diseases (eg gastro, pancreatitis), we generally run a full blood profile that includes markers of kidney disease.

Blood parameters that tell us about the kidneys’ ability to remove metabolic wastes are:

Creatinine – this is a waste product of muscle breakdown and is always present in the blood at pretty steady levels unless there is a problem with kidney function, when it goes up

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) – this is a waste product of protein metabolism and is also always present in the blood, but unlike creatinine, it is influenced by factors such as dietary protein, intestinal bleeding and hydration and so is less accurate

Symmetrical dimethylarginine (SDMA) – is a newer test that also elevates when the kidneys aren’t able to clear wastes, except this one becomes abnormal much sooner than creatinine and allows for earlier detection

Although SDMA now allows for earlier detection, for blood parameters to be elevated, your cat has to have lost about 75% of her nephrons. So we can’t really say that we can detect early disease – we don’t yet have the ability to do that in any species.

When creatinine, BUN and SDMA are above normal, your cat is said to be azotaemic. If these have built up to a point where your cat is ill from them, this is a condition called uraemia. That is, it’s possible to have elevated kidney parameters and still feel okay. And all cats are different when it comes to what level they start feeling unwell.

As well as diagnosing renal disease, these parameters are used to determine the grade and stage of disease.

The rest of the blood picture can help us differentiate between acute and chronic. For example, with CKD we may also see anaemia (due to the lack of EPO) and high phosphorus levels.

Urine testing

Urine testing (called urinalysis) may include one or more of these:

urine specific gravity (USG) – this tells us the concentration of the urine. When the kidneys are working properly, they are always balancing the amount of water in our systems. To do this they’re either conserving water (concentrating the urine) or getting rid of excess water (diluting the urine). They’re never really doing nothing, so if we find a USG that indicates neither concentration nor dilution has taken place, we worry about kidney function

dipstick – you might have seen one of these when you’ve gone to your GP. A dipstick is a paper strip with little squares of on it that are impregnated with reagents that change colour when they come into contact with different things in the urine (eg blood, glucose, ketones, urobilinogen, protein)

cytology – this is where we spin the urine in a centrifuge to make all the solid bits go to the bottom, then we take those, put them on a slide and look at them using the microscope. We’re looking for blood, bacteria, white cells, any abnormal looking cells and things called casts (which are like molds of the nephron tubes)

culture and sensitivity – this is where we send the urine away to a lab for them to look at it and also ‘incubate it’ to grow bacteria (that’s the culture part), they also grow the bacteria in the presence of antibiotics and see what stops them growing (ie what the bacteria are sensitive to). If we’re going to do this test, we usually get the urine directly out of the bladder with a needle and syringe. This means our sample should not be contaminated by bacteria in the genitals or on the skin.

How is kidney disease treated?

Both acute and chronic kidney disease have some similar consequences: changes in blood volume, dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, change to urine production, acid-base imbalance, anorexia, vomiting, and heart and brain disorders. General treatment aims to address these consequences.

I’m going to give you way more info here than you’ll ever need. But hopefully, it will give you some idea of what to expect (and the costs that might be involved) if kidney failure treatment is recommended for your cat. Feel free to skim read!!

treatment of acute kidney disease

With acute disease we’re treating the general consequences of kidneys failing to work. We’re also trying to limit ongoing kidney damage, improve blood flow through the kidneys (perfusion) and enhance recovery of kidney cells. How we do this depends somewhat on the cause of the injury and on the stage of disease.

There are three stages of AKD:

Initiation – this occurs during and immediately after the injury to the kidneys (but typically before we see clinical or laboratory signs of disease). It usually lasts around 48 hours. Treatment during this stage tends to have the best chance of a good outcome

Maintenance – this is when we see azotaemia (increased kidney parameters in the blood) and/or uraemia (clinical illness associated with azotaemia). We might also see a reduction in urine production (either oliguria which is <1 ml/kg/h or anuria which is no urine). This stage can last for days or weeks – and therefore involve lengthy treatment in hospital (and we can’t tell whether the pet will recover or not). Not that the severity of the azotaemia doesn’t affect the prognosis but an improvement within 3 days of therapy carries a better prognosis

Recovery – during this stage, blood parameters improve as the kidney tubules undergo repair (or undamaged ones become super efficient). Apart from improving blood work, we often see a significant increase in urine production (called polyuria) due to both partial restoration of kidney function and osmotic diuresis as all the accumulated toxins are flushed out. Renal function may return to normal (can take up to 6 months) or we may have chronic renal dysfunction (occurs in 30–50% of cats that survive AKD)

Note that not every pet will reach the recovery stage – many patients will die of acute renal failure despite treatment.

A typical scenario: A cat is presented after known or suspected ingestion of some parts of lily (or water lilies kept in). If ingestion occurred within 2 hours, we’ll try to induce vomiting and may administer some activated charcoal. We’ll then start IV fluids (and probably take some ‘baseline’ bloods) and continue fluids for at least 48 hours (ie the initiation phase). We’ll take some (more) blood and look for elevations in creatinine, BUN and SDMA. If we don’t see elevations, our patient can go home. If we do see elevation, treatment and monitoring continues (see below).

Treatment of AKD may include several of the following:

Intravenous fluid therapy – this means putting your cat on a drip. But it’s not quite that simple. When we give fluids to a patient with AKD, we need to:

calculate and replace the fluid deficit – this is the amount of fluid we need to put into the patient to reach normal hydration. We have to be careful how fast we replace this fluid in order not to cause more complications (times vary from 4–24 hours depending on various patient factors)

work out the best type of fluid to use during the different phases of therapy

determine the amount of fluid we need to continue to give after rehydration, which is based on several factors including the amount of urine that is being produced, ongoing vomiting or diarrhoea, other disease (eg heart disease, diabetes)

monitor closely for urine output, signs of overhydration, electrolyte changes, acid-base changes and kidney parameters

Manage urine output – once we’ve rehydrated the patient, we should see urine production normalise (ie the cat should produce 1–2 ml/kg/h urine). If the urine output is less than that, we may be dealing with kidneys that can’t respond to fluids alone or obstruction to urine flow from the kidneys. If there’s no obstruction, additional therapies may be tried including:

giving a bolus of fluids (eg 5 ml/kg over 10 minutes) to see if we can induce diuresis (increased urine production) within 10–30 minutes. If this doesn’t work, the patient likely has ‘volume-unresponsive AKD’ and further fluids are unlikely to help

diuretics (eg frusemide, mannitol) – these have largely gone out of favour because they are most likely to help during the initiation phase (which is often missed with veterinary patients), they haven’t shown to improve outcomes in people and they can have significant side effects

drugs that dilate blood vessels to kidneys (eg dopamine) – again these have gone out of fashion as studies have not shown any benefit and they are complex to administer appropriately

Manage electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities – this includes monitoring and adjusting levels of:

potassium – if your cat can’t produce enough urine, potassium levels can build up in the blood. This can cause severe problems such as life-threatening heart rhythm issues. Intravenous fluids often help reduce potassium, but we might also need to use other drugs to protect the heart such as calcium gluconate, frusemide or insulin. Potassium may also be too low in kidney patients, requiring supplementation in the intravenous fluids

calcium – particularly with lily toxicity, we can see low calcium levels in the blood. This can cause muscle tremors, facial itchiness, cramps, aggression, disorientation and even seizures

acid-base – when the kidneys don’t work, the blood can become too acidic, which can affect all other metabolic processes. Intravenous fluids usually resolve this problem

Management of uraemic complications – when the kidneys fail to excrete toxins, they can build up to levels that result in oral, oesophageal and stomach ulcers, nausea, vomiting and anorexia. Medications used to reduce these include:

antinausea drugs (eg maropitant. metoclopromide, ondansetron)

appetite stimulating drugs (eg mirtazepine, which is also an antinausea drug)

gastroprotectants (eg antacids like omeprazole, and ulcer meds like sucralfate)

pain relief (eg buprenorphine, methadone)

Nutritional support – we need to make sure we enough nutrients into our patient to prevent weight loss, support kidney repair and help the immune system (and reduce secondary infections). This may involve tube feeding if we cannot get enough nutrients in orally.

Managing cardiovascular, pulmonary and neurologic complications – we won’t go into all of these, just know they can happen and when they do, they can be very difficult to manage.

Okay, that’s enough of AKD treatment (although, there’s a lot more I could write!) Let’s move on to the much more common CKD treatment.

treatment of chronic kidney disease

In many ways the treatment of CKD is simpler than AKD – we’re not trying to reverse the process. We’re looking to address symptoms that affect quality of life and hopefully slow down the progression of the disease. Treatment varies with each patient and with the stage of disease.

There are four stages of CKD:

Stage 1

Creatinine <140 umol/L

SDMA >14 ug/dL

no azotaemia

Stage 2

Creatinine 140–250 umol/L

SDMA is >14, but if SDMA is ≥25, we should consider this cat is in or moving into stage 3

mild azotaemia

Stage 3

Creatinine 251–440 umol/L

SDMA is ≥25, but if SDMA is ≥45, the cat may be in or moving into stage 4

moderate azotaemia

Stage 4

Creatinine >440 umol/L

SDMA markedly increased

severe azotaemia

Other factors like blood pressure and the amount of protein in the urine also affect the staging of CKD.

Treatment is based on stage of disease include the following:

Stage 1 treatment

discontinue (if possible) any medications that may negatively affect the kidneys

identify and treat any pre-renal or post-renal abnormalities

rule out treatable conditions like kidney infection (pyelonephritis) and kidney stones

avoid or manage dehydration (eg have fresh water available at all time and consider giving fluids under the skin (subcutaneous) or intravenously

monitor and treat high blood pressure (as needed) – this may involve reducing the salt in the diet and/or giving medication (eg amlodipine +/- benazepril)

monitor and treat protein loss in the urine (as needed) – this may involve looking for any associated disease process that can be treated as well as giving medication (eg benazepril)

change the diet to a prescription renal food (unless the patient’s phosphate level is normal, when we might just stick with a senior food, as these patients can develop high calcium levels on a phosphate restricted diet)

Stage 2 treatment

all of stage 1

reduce phosphate intake – elevated phosphate levels are associated with reduced life span. Even though many patients in this category might still have normal phosphate levels in their blood, the hormone that controls phosphate is likely to be elevated. The usual way we control phosphate intake is with a prescription renal diet. If this isn’t enough to reduce phosphate, we can use a phosphate binding drug (eg aluminium hydroxide, aluminium carbonate, calcium carbonate, calcium acetate)

monitor potassium levels and supplement if needed

Stage 3 treatment

all of stage 1 and 2

treat symptoms that are negatively affecting quality of life such as dehydration. nausea and vomiting and anaemia

Stage 4 treatment

all of stage 1, 2 and 3

often these patients require a period of hospitalisation to control symptoms

If there is an inadequate response to therapy, euthanasia must be considered (as it should be in any case where we cannot alleviate suffering)

How are cats with kidney disease monitored?

Once a cat has been diagnosed with kidney disease but is well enough to go home, we need to keep an eye on them on an ongoing basis.

At home, you need to monitor:

water intake and urine output

appetite

nausea and/or vomiting

weight

lethargy

Regular monitoring in the clinic will also be needed. The type and frequency will depend on the stage/severity of disease and will likely include:

general physical examination including weight and hydration status check

blood testing

urine testing

blood pressure monitoring

assessment for concurrent illness